If you think your best friend will look out for your best interests after you check out of this life, then listen to the tale of what happened to Dorothy Parker’s ashes after she died in 1967. We all know Parker had a deep affection for death-inspired imagery. She was asked once to compose her epitaph: “Excuse My Dust,” she wrote. Later, she penned another: “This Is On Me.”

Her ashes are in Baltimore, Maryland. What is the true Parker epitaph? Read on…

Four suicide attempts never succeeded for Dorothy Parker. When she turned 70, she told an interviewer who asked what she was going to do next, “If I had any decency, I’d be dead. All my friends are.” But death waited until she was 73, and a fatal coronary came on June 7, 1967. She was living in the Volney; a residential hotel located at 23 East 74th Street between Fifth and Madison avenues on New York’s fashionable Upper East Side.

Her will was plain and simple. With no heirs, she left her literary estate to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. She’d never met the civil rights activist, but always felt strongly for social justice. She named the acerbic author Lillian Hellman as her executor.

Parker didn’t want a funeral, but Hellman held one anyway, and made herself the star attraction. Her memorial ceremony was held at the Frank E. Campbell funeral home, on the corner of East 81st Street and Madison Avenue, just seven blocks from the Volney.

Within a year of her death, Dr. King was assassinated, and the Parker estate rolled over to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. To this day, the NAACP benefits from the royalty of all Parker publications and productions.

She was cremated, and this is where the story takes a sharp right turn. Parker was cremated June 9, 1967, at Ferncliff Crematory in Hartsdale, New York. Hellman, who made all the funeral arrangements, never told the crematory what to do with the ashes. So they sat on a shelf in Hartsdale. Six years later, on July 16, 1973, the ashes were mailed to Mrs. Parker’s lawyer’s offices, O’Dwyer and Bernstein, 99 Wall Street. Paul O’Dwyer, her attorney, didn’t know what to do with the little box of ashes. It sat on a shelf, on a desk, and for 15 years, in a filing cabinet.

Hellman went to court to fight the NAACP over Parker’s literary estate. Hellman lost in 1972 when a judge ruled that she should be removed from executorship. Hellman was adamant that she get Parker’s money, and came out of the mess painted as a racist. She was sure the will was supposed to give her a huge sum. Hellman said, “she must have been drunk when she did it.”

In 1988, someone figured out that Mrs. Parker’s ashes were unclaimed, 21 years after her death. New York tabloids ran stories and readers sent in letters about what should be done with the dust. But the NAACP stepped in and took the box from Paul O’Dwyer’s drawer. The NAACP built a memorial garden at the national headquarters in Baltimore and interred the ashes there.

Address of Memorial Garden

4805 Mt. Hope Drive

Baltimore, MD 21215

GPS: 39.344432, -76.708965

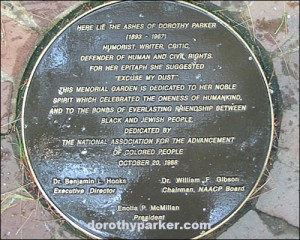

On Oct. 20, 1988, the president of the NAACP, Benjamin Hooks, dedicated the memorial garden on the office property. The brownish brick memorial is circular, meant to recall the Round Table, according to designer Harry G. Robinson. The memorial stands in a small grove of pines outside the offices, with pine needles and pinecones scattered around the ground.

There is a round urn that holds the ashes, and an inscription on the top. This is what the real Dorothy Parker epitaph says:

Here lie the ashes of Dorothy Parker (1893-1967) Humorist, writer, critic, defender of human and civil rights. For her epitaph she suggested “Excuse My Dust”. This memorial garden is dedicated to her noble spirit which celebrated the oneness of humankind, and to the bonds of everlasting friendship between black and Jewish people.

What does that last sentence mean? You should read Parker’s 1927 New Yorker short story “Arrangement in Black and White” to know. Parker was way ahead her time in pushing for social justice. She may be more often recalled as a drinker and wit, but for many, she was a pioneer in the civil rights movement and her memorial is a testament to it.

All photos courtesy of Kathy Gadziala.