By Kevin C. Fitzpatrick

March 15, 2006

It is May 1944 and President Franklin D. Roosevelt is in the White House. Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia is running New York City. Across the Atlantic, approximately 176,000 Allied troops are making plans for history’s greatest military air and sea invasion. The world is at war and there is suffering everywhere.

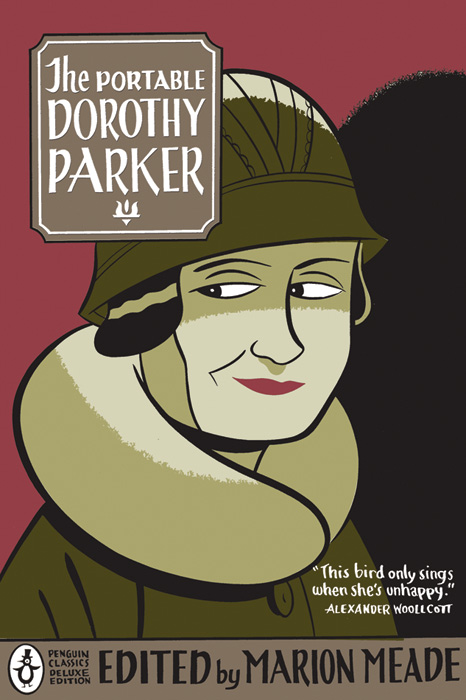

Meanwhile, in a stone farmhouse near Pipersville, Pennsylvania, Dorothy Parker, 50 years old, is keeping busy. The former member of the Vicious Circle is preoccupied with two things: writing letters to her husband, Lieutenant Alan Campbell, and collecting together material for what would become her last book. Viking Press, her longtime publishing house, was getting into the war with a series of small books they nicknamed “portable” editions. Due to wartime conservation restrictions they printed the books on cheap recycled paper. Among the first ones — including The Portable World Bible, The Portable John Steinbeck, and The Portable Walt Whitman – was a slim volume of 544 wafer-thin pages: The Portable Dorothy Parker.

Paging Through History

Six decades later, all of those people are gone, and so is Viking Press, swallowed up by its British corporate entity, Penguin. Lately the publisher has been revamping its “classics” line and among the first in its “deluxe editions” is Dorothy Parker. Just like she rubbed shoulders with God, Steinbeck and Whitman in the 1940s, the new Parker book is being released in the same week as new editions of Paul Auster, Hans Christian Andersen, and Voltaire.

The history of this popular collection of Parker’s short stories and verse is a checkered one. In 1944, Parker herself chose the material to include (or forget). Her good friend, Somerset Maugham, penned a warm introduction. He gushed,

One of the charming things about Dorothy Parker is that when the door of opportunity flies open she is there at the threshold ready to make the most of the God-given moment. She seems to carry a hammer in her handbag to hit the appropriate nail on the head. She has a rare quickness of mind.

The flyleaf dedication was to Campbell.

It was this 1944 edition that Parker’s readers could find until the early 1970s. By this time, Viking Press was re-releasing its line of “portables” and Parker was in line for an updating. Someone called someone and they dug up Brendan Gill. This curmudgeon — one of the longest-serving members on William Shawn’s staff at The New Yorker — knew Parker only through cocktail parties. Gill was hired to introduce a new edition. He wrote:

The world would have said that she had every opportunity to fulfill her talent, and now she lived alone, with a raspy little concierge of a dog, in a hotel room in Manhattan and waited for nothing and hoped for nothing and got through the day, often enough with a bottle.

Later, Gill writes, “She had been tiresome when she drank in youth, and with age she could scarcely be expected to improve; the occasions for drink were not merry ones.” So much for his literary criticism – Penguin’s publisher allowed this “introduction” to remain in print for more than 30 years.

This second edition of the Portable Dorothy Parker is the one most readers are familiar with; it has been in print since 1973, with Brendan Gill’s name plastered on the cover. Editors at the time added a hodge-podge of Parker drama criticism, book reviews, and essays. The “portable” grew to 610 pages.

Re-Birth in the 21st Century

Thirty-three years later – missing the book’s Golden Anniversary by two years – Penguin Classics has honored the book with the attention it deserves. A new editor: Marion Meade, author of the bestselling Parker biography, What Fresh Hell is This? (Villard, 1988). She tossed out the Gill introduction and crafted a new one. She writes:

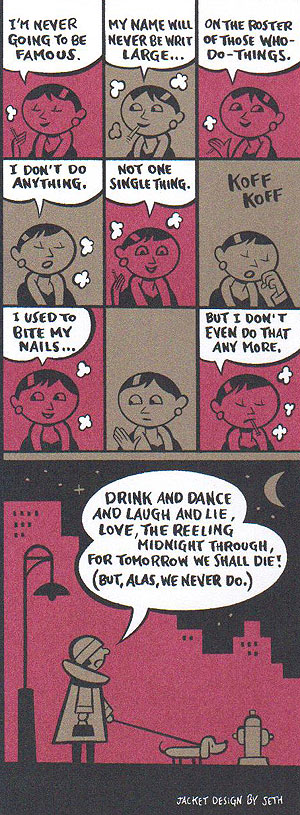

We do not care that she failed to write the Great American novel. Or the Great American Poem because we value her writing for its uniqueness. Her work has never been out of print, an extraordinary accomplishment in itself. Readers of all ages, including those who have no particular interest in the 1920s, continue to find her stories irresistible.

Meade also carefully pared down the back third of the book, excising numerous superfluous bits and adding in new Parker material. Gone are book reviews of tomes even ardent bibliophiles never heard of; gone are drama reviews that seemed a bit dust-covered.

This is the edition that Parker fans will want to own. They will want to buy it and press it on friends they are eager to convert to the Parker Faithful. The book looks gorgeous and the editing decisions have shaped a much-improved edition. In addition, hats off to the publisher for resetting the entire book in a fresh-looking typeface.

Meade faced a challenge when she accepted the job to edit this classic book. The “portable” could not grow in page size, so she would have to cut out material. Leaving alone the material that Parker herself arranged in 1944 – Parker chose the short stories and poems she wanted to be remembered by – Meade could only have wiggle room in the 1970s decisions from the Viking Press area. Luckily for readers, there were numerous fair-to-middling selections from Parker’s oeuvre. She picked out many lost gems. Included here for the first time:

“Such a Pretty Little Picture,” Parker’s first short story, from 1922;

“Interior Desecration”, a hilarious piece she wrote for Vogue in 1917 on interior design;

“My Hometown,” a love letter to New York City, from McCall’s in 1928;

A review of “Ziegfeld Follies of 1921”, where she talks about everything but the show;

Personal letters never published before, to her father, Scott Fitzgerald, Alexander Woollcott, Robert Benchley, and many others.

It isn’t often that one can write about a beloved book and say that a publisher has made it better. But in this instance, the newly revised “Portable Dorothy Parker” is a book that all Parker fans simply must own, must give to friends, and must display in the front windows of their homes and apartments.

Kevin Fitzpatrick is the president of the Dorothy Parker Society. He is the author of “A Journey into Dorothy Parker’s New York” (Roaring Forties Press, 2005). He leads walking tours devoted to Mrs. Parker and the Algonquin Round Table.