By Kevin C. Fitzpatrick

April 25, 2008

Dorothy Parker collaborated on The Ladies of the Corridor with playwright Arnaud d’Usseau. He was 27 years younger than Parker, and had co-written two successful plays: Tomorrow the World, which ran for 500 performance at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre in 1944-1945, and Deep Are the Roots, which played almost as long at the Fulton soon after. His longtime writing partner was James Gow, and the team went to Hollywood. It was there that he met Dorothy Parker after World War II. D’Usseau was an interesting character. He was born April 18, 1916, in Los Angeles to a family in the movie business. After his mother died when he was a child, his father, a screenwriter, put Arnaud and his younger brother into an orphanage. At boarding school, he learned to write, and turned to playwriting and screenplays during the Great Depression.

How did you happen to meet Dorothy Parker?

Jimmy Gow, with whom I worked, got an assignment in Hollywood. I don’t know what the year was. Around 1948 or 1949. I went out by myself. I was married but my wife decided she didn’t want to come with me. She was a painter and was living in New York. So I went out and I took an apartment at the Chateau Marmont. It was a place that wasn’t as swanky as the Garden of Allah. You hear about that one, the Garden of Allah, because it is where Benchley and Fitzgerald stayed. But right opposite was the Chateau Marmont, not as expensive and not as glamorous, on Sunset Boulevard. We used to see each other in the elevator. She had a dog, and we talked about that. I got lonely and asked my wife to come out and join me. Which she did. One night we saw Dorothy in the elevator and we asked her to come for a drink. She was delighted. She had a dog that belonged to the guy she was living with, called Flic, a beautiful boxer with a white blaze on his forehead. So after awhile she was coming almost every night for dinner. Or we’d go over to The Player for dinner. On the weekends we’d play anagrams. We would have parties, and we became friends.

How did the collaboration between you and Parker begin?

Jimmy and I finished the assignment and we came back to New York. It had become our home and we bought a house here. Several years went by. Jimmy Gow died. We lived on 58th Street and didn’t hear much from Dorothy. She didn’t write much but she sent telegrams, signing them in the dog’s name. Then she came East. She called us and we said to come to dinner. She did and said, “Let’s write play,” so I said fine. She was fascinated by actual case histories of British murder trials and the (true crime) books. She thought we could get a story out them. At one point I said to Dorothy I didn’t want to do this, because I did a lot of “B” pictures like this in Hollywood. I wasn’t really interested. Then I told her an idea I tried out on Jimmy Gow, which he didn’t pick up on. It was what happens to the women in America whose husbands die when they are in their late forties and fifties, and they are left alone for another 20 years. I had seen this happen to my sister-in-law whose husband died. She didn’t know what to do. She tried to become a secretary. Her children were raised. So she got cancer and died, she was just totally lost. I looked around the neighborhood and began to realize that there were a whole group of women having dinner at 5 o’clock at Schraft’s, and were coming out of the bars drunk, all beautifully and elegantly dressed. All totally unhappy because of the loneliness. Of course Dorothy picked up on it right away. She tried to write a long poem about this. So we decided to write about this, and we were off and away. That’s how we started to write The Ladies of the Corridor.

Where did the title come from?

I found the title, actually. We were looking around for a title. I don’t know what made me read Eliot. It is from “Sweeney Erect”:

The ladies of the corridor

Find themselves involved, disgraced,

Call witness to their principles

And deprecate the lack of taste

But of course it’s a wonderful title, with two marvelous words, “ladies” and “corridor” which is what you look for in a title, strong, good words. It said actually what we were planning to write it on.

How much of the Volney Hotel is in there?

That’s funny, because people thought we got the idea from The Volney. Because we didn’t. We started writing the play when she was living at the Windham, I think. That became too expensive so she moved to the Maurice. So we continued to write it at the Maurice. Then she left the Maurice and she went to the Volney. When we walked in, she said, “This our set. This is our play.” And of course it closely resembled it. We were still writing the play. It even had the salmon pink gladioli in the lobby. Most of them did in those days, they all had gladiolas. And pink.

How did you two collaborate on the writing?

She started to write a long poem about it. And what she recognized, and what I knew, because my sister-in-law had this experience thoroughly, was that the big enemy was loneliness. We had this very quickly for our theme. It took us a long time to work out the structure. For a long time we were in one room. And one day after about two months, I said, “Dorothy, we have our characters, and we have enough situations, but how can we depict loneliness with just one set, with people popping in and out all the time?” And it was then that we decided to open it up, which we did, and it became this five-set play with other rooms, the corridors. It made it very expensive to run.

Parker said later in the Paris Review that The Ladies of the Corridor was the only thing she wrote that she was proud of. Do you believe that?

She was very proud of it. I don’t think it was an exaggeration. I think she was proud of “Big Blonde,” I know she was. I think she was proud of “Arrangement in Black and White.” One of the reasons she said that was a lot of it was a summation for her of all that she thought and felt. At one point we began to discuss who would get the first name on the play, and she wanted to give it to me because I was a playwright and she didn’t consider herself a playwright. And I said, “No, Dorothy, basically this is your material. I did contribute a lot in terms of the structure and to the problems of playwriting. So I insisted her name come first. So this was a summation and she was saying a lot of the things she wanted to say. People always thought that I did the plot and she did the dialogue, which is ridiculous. We worked out the story between us and then wrote it out line by line.

Who did what?

We both did everything. For instance, one thing I had read about, and she knew about, was how many women threw themselves out the window. We used to see it in the tabloids all the time in the Mirror, and the Daily News. It would happen four or five times a year. So we decided to have a suicide. That belonged in the story. For a long time we were opening with that (laughs). I said to her, “Dorothy, if we open with this, where do we go?” Now it comes at the end of the play.

You sound protective of Dorothy. What made you feel so protective of her?

Well, it is part of my temperament. I was raised with a younger brother and we had no family until I was 14. So I was in charge of my younger brother, we were in an orphanage together and later at boarding schools. I always had to look after him. I didn’t realize this about myself until much later. So I have to protect (people), especially those that I love. I have to protect my wife; I have to protect my children. I am quite happy to do it. And anyway, I had great admiration for Dorothy. Even though she was 27 years older than I was, she was of another generation. People really didn’t understand her.

How so?

Oh, in so many ways. We’d go to a party together and once people knew she was Dorothy Parker they’d start to insult her. It was just outrageous. And if she were sober she would just take it, and if she wasn’t sober she’d let them have it. She was very sharp. But believe me, always; at least when I was the witness, she was the one who was provoked.

How would they insult her?

Oh, first of all they wouldn’t believe it was she. And then they would say, “If you’re so smart, make a joke.” Or they would try to be funny themselves, and be rude… there was so much jealousy. Dorothy got a good deal of that. And of course, she was marvelous company.

How so?

She was fun. She was bright. She was tremendously sympathetic. People always thought of her as just a wisecracker, but there is a great deal of difference between wit and wisecracking. Wisecrackers are usually defensive. And she was witty. In the Twenties she had to wear this tough veneer, but she was serious. She was serious politically.

How was the cast of the Broadway show?

Walter Matthau was not only a good actor, but also solid. He once told me, “You gave me the most valuable information I’ve ever gotten in acting.” I asked what, and he said, “When Edna (Best) was throwing herself around, I asked you what should I do, and you said, ‘Do nothing.’ And he did… Walter just sat there… and it worked out very well. We had a very good cast. We had Betty Field. We had Frances Starr, who had been a big star before the First World War. It was well produced. But it should have played three matinees because the women recognized it immediately.

What else about Parker do you recall?

She was frightened of death. Fascinated by death. I remember once, we were at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and she stopped at a painting. It was the Rembrandt of a young Jesus. She thought that was the best painting in the whole museum, she was just fascinated by that. She was very moved.

Thank you.

***

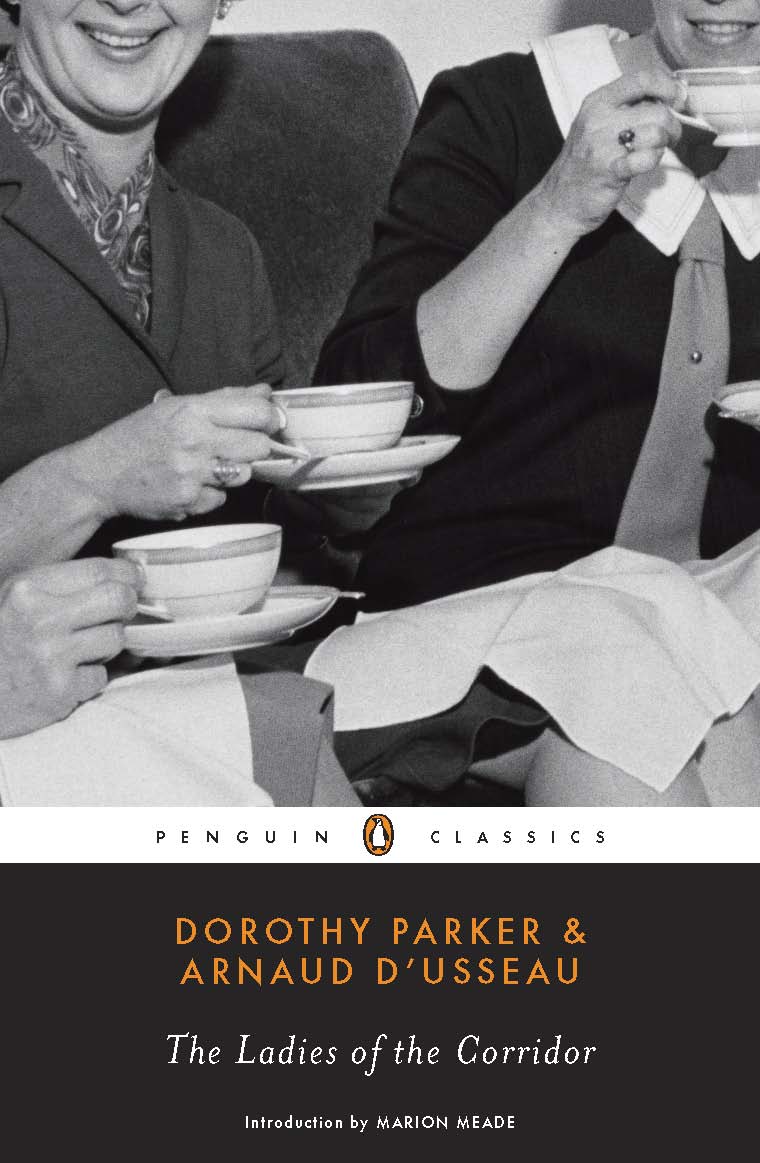

The Ladies of the Corridor is on sale now in bookstores everywhere, and online. [Buy via Amazon]

2008 Interview with biographer Marion Meade about The Ladies of the Corridor.

2008 article about re-release of The Ladies of the Corridor by Penguin Classics.