The quintessential New York author would appear to be Dorothy Parker. Raised on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Working at Vogue when she was 21 and writing for Vanity Fair at 24. Attending the birth of The New Yorker with her pals of the Algonquin Round Table. However, was she the most successful and perhaps happiest while living in Hollywood?

It occurs to me that it was in California that she reaped the most benefits of her fame. After 20 years as a Manhattan wage slave, selling poems, reviews, and short fiction to newspapers and magazines, it was only when she landed in Hollywood that she was paid well and enjoyed herself.

Parker spent the 1920s writing tens of thousands of words for periodicals. She had a monthly drama column for Vanity Fair and Ainslee’s. When The New Yorker launched in 1925, she wrote for it. She sold poems to magazines and short fiction to The Smart Set, The Bookman, and others. During the heyday of the Algonquin Round Table, beginning in 1919, she was always under a deadline. After the collapse of her first marriage, to stockbroker Eddie Parker, she was depressed, lonely, and suicidal. It took vacations to the French Riviera with the literati in the late 1920s to get her out of her funk. After trying Paris she tried Los Angeles.

She missed the stock market crash in October 1929 because she was making her first attempt at screenwriting. Parker accepted a $300 a week contract for three months at MGM. Stuck in a Culver City office, she was assigned to write dialogue for melodramas. One Hollywood yarn Parker told a gossip columnist was that she was so bored, she begged studio sign painters not to letter her name on her office door. She had them paint “GENTLEMEN” instead. Her contract complete, Parker went back to New York without earning one screen credit. She resumed writing short stories and living in hotels. The next chapter of her life was about to begin.

Around 1932 Parker was introduced to Alan Campbell, a striking actor-writer from Virginia, who happened to be 11 years her junior. She fell madly in love with the handsome Southerner, and the two soon moved in together. With her dogs, messy finances, and bad habits, Campbell soon took over her life. He was her lover, manager, cook, and bartender. It was a perfect match.

In the summer of 1934, Parker accompanied Campbell to Denver, Colorado, where he was contracted to appear in summer stock at the landmark Elitch Gardens. This would be the end of his acting career, but the beginning of their thirty-year life together as partners. The local press was thrilled to learn Dorothy Parker had moved to town, but when had she remarried, they asked? Trapped in lies, the couple bounced to New Mexico and were married before a local magistrate.

By this time, many of her friends from the Algonquin Hotel were established in California. The couple, their dogs, and all their worldly belongings, packed into an open-topped Ford and headed for Hollywood to join them. Parker was reunited with her friends Robert Benchley, Herman Mankiewicz, Laurence Stallings, and Donald Ogden Stewart as New York refugees in the new film capital. Screenwriter Charles MacArthur, an ex-lover, also went West. “Hollywood money is something you throw off the ends of trains,” he said, and Parker subscribed to this notion.

The couple accepted a contract from Paramount as a screenwriting team; guaranteeing Campbell $250 a week and Parker $1,000 (about $26,000 today). Parker had never seen so much money. For the first time her life, she could buy a house, car, and designer clothes. She and Campbell were soon living in fine homes, going to private clubs, and flying coast to coast. Parker indulged herself with expensive hats and furs, paid for with studio money. Echoing MacArthur, Parker said, “It isn’t real money. It isn’t. I think it’s made of compressed snow. It just melts in your hands.” A couple years later they signed new contracts for $5,000 a week, at the height of the Depression, when the average family earned $1,500 annually.

Most of Dorothy Parker’s residences in Los Angeles are still standing, from the Chateau Marmont to a charming Beverly Hills house on North Roxbury Drive, where Jimmy Stewart was a neighbor. One location that met the wrecking ball was the Garden of Allah, a home for many years to the New York crowd. The fabled hideaway, once the property of actress Alla Nazimova, had 25 bungalows surrounding a lotus-shaped swimming pool. Among the other residents were John Barrymore, Robert Benchley, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Katharine Hepburn, Ernest Hemingway, Somerset Maugham, and John O’Hara. “A world within the world of Hollywood,” wrote Sheilah Graham, “It was an oasis for the talented residents who found sanctuary from the frustration of their work in the studios.” The Garden, at 8152 Sunset Boulevard at Crescent Heights, is soon to be developed into shops and residences.

Their first year in Hollywood, Parker and Campbell worked on Here is My Heart, a Bing Crosby picture, and One Hour Late, a madcap romantic comedy. Both were forgettable, which can describe the majority of their nearly forty screenplays. Campbell sat at the typewriter and crafted the scenarios. Parker was nearby, usually knitting, and her husband might ask, “Shall we make the mother a washerwoman?” Parker might reply, “Oh yes, by all means, a washerwoman.” Parker would read over what Campbell wrote, make edits and add dialogue, elevating the work.

In 1936 the nascent Screen Writer’s Guild was forming, and Parker played a part in getting it off the ground (today it is Writers Guild of America, West). At her rented mansions, Parker hosted fundraisers for scores of political causes. One was to raise money to defend the Scottsboro Boys, eight young black men charged in 1931 with the rape of two white women and sentenced to death in Alabama. She fundraised for the relief for Spanish Civil War refugees, anti-fascist campaigns, and spoke out for civil rights. Along the way her FBI file grew to be three inches thick and she ended up on the blacklist.

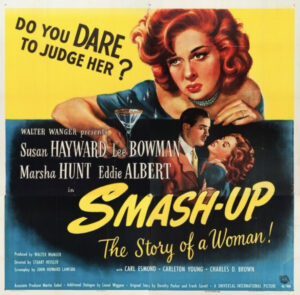

Parker earned just two accolades for her screenwriting days. She was nominated, but didn’t win, two Academy Awards. A Star Is Born (1937) and Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman (1947) are among the best scripts she worked as a collaborator on. Some film buffs suspect her fingerprints are on Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life (1946).

Parker and Campbell divorced after World War II, but were reunited a few years later and remarried in 1950. Parker, in her sixties, moved back and forth between Los Angeles and New York, until she settled down with Campbell again in a tiny bungalow in West Hollywood on Norma Place. The last script they worked on was slated for Marilyn Monroe, who died when it was being developed. Not long afterward, Campbell died of an overdose, prompting Parker to return to New York for good. She died there of a bad heart in June 1967. She was 73.

Parker said many pithy things about Los Angeles, but more than likely didn’t say it was “72 of suburbs in search of a city.” Today there is only one spot in Los Angeles that remembers Dorothy Parker’s 30 years as a resident. Her visage is part of a mural, a painting of early female screenwriters, at the headquarters of the Writers Guild of America on West Third Street.

Originally published Dec. 6, 2013, for the Huffington Post.