The best and longest radio interview Dorothy Parker ever gave has been rediscovered and is now available to listen to here for free. Thanks to researcher-collector Mark Rosenberg, who donated a copy to the Dorothy Parker Society, fans can hear Parker talking about subjects as diverse as Truman Capote releasing In Cold Blood and Frank Sinatra meeting Robert Benchley. The March 3, 1966, session was recorded inside her apartment in the Volney Hotel, and street noise is faintly heard through the windows.

“Men seldom make passes/At girls who wear glasses. Oh, I wish I had never written those silly, lying words,” begins the groundbreaking interview. Parker was 72 years old when she said this. The tape is 70 minutes of Parker cracking wise and reminiscing, while also giving keen observations of 1960s New York City.

The stories around this long-lost 70-minute recording are legendary. While the existence of the interview was known, a copy of it was not. The interview was conducted by Richard Lamparski and broadcast on WBAI, a non-commercial station in New York. Lamparski—who is still very much alive today—said he loaned the recording to the first Parker biographer, John Keats, who used it to some extent in You Might As Well Live, The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1970). “Neither John Keats nor Marion Meade, who also utilized my radio program for her book Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This? (1987), asked me a single question about the makings of the transcription or my relationship with and/or observations of their subject,” Lamparski recounts in Manhattan Diary. Neither biographer interviewed Lamparski, who spent six months taking Parker to the movies. He won her over.

The difference between the Lamparski interview, and the print interviews Parker sat for with Gloria Steinem and Michael Stern the previous year, is that this interview is a true recorded give and take, with follow-up questions and succinct replies. Lamparski really did his homework to prepare for this day, and it shows. He does not flatter Parker as much as one might think would be needed. “Your books are as popular as any others in college bookstores,” Lamparski says. “I go out and do interviews once or twice a week, and I have for more than a year now, and you are the only one that I have said I was going to interview that I really got a rise out of every single person I know. Everyone was impressed.” Parker took the bait. “It absolutely astounds me, and makes me grateful and frightened at the same time,” she replied.

The pair spoke at length about a wide range of topics, from dogs, to William Randolph Hearst, to Parker’s television set. “I hate this stuff,” she said. “I sit and listen to soap operas,” she admitted. Lamparski was also very good at running a series of quotes (and misquotes) by Parker for verification. Of having quotes and stories attributed to her, Parker said, “I should say two or three times a day. They were dreadful.” She does confirm that she asked for “MEN” to be painted on her office door in Culver City.

Lamparski got Parker to speak at length about her time in Hollywood, which elicited comments about not liking the town or screenwriting. She seemed to forget she and Alan Campbell were nominated for an Academy Award for A Star Is Born; and she loathed the 1954 remake starring Judy Garland and James Mason. She infers that the original story was based on factual events about a silent movie star and his wife. Lamparski pushes her confirm the ending of the film was based on an actual suicide: “It was an actor, it was Hollywood, and there was a sunset, now what are you going to do?” she answers.

Parker dishes on many names from her past, including playwright Elmer Rice and fellow author Fanny Hurst, who Parker sent a fan letter to. She says she was most proud of writing The Ladies of the Corridor, and was disappointed in Candide (1956), pointing the finger at “Lenny” Bernstein. “It was so overproduced you couldn’t tell what was going on at all…there were too many geniuses.”

Lamparski asks Parker about specific stories and moments in her career. “I gave up writing verse shortly after you were born because I wasn’t getting any better,” she said. “This magnificent gesture went totally unnoticed, I may say.”

While she does not miss working in Hollywood, she did miss being a book critic for Esquire magazine: she loved the complimentary copies and it gave her a starting point to write something. Parker had to quit because of old age illnesses. She also says she never had the stamina to write a novel because “I am a short distance” writer. She speaks at length about current authors, such as Saul Bellow and Truman Capote. In fact, his book In Cold Blood was released in January 1966 and the interview was mere weeks later. The book was on her table, and she gave it her highest praise.

“I hated to end it, hated to turn a page…I thought it was enormously sad, enormously sorrowful. Not just—and I don’t mean to sound as callous as I do—not just [for] the family but those two young men.”

At several points in the interview, Lamparski dances around the Algonquin Round Table, which Parker had warned him off the topic, because she was sick of it. He asked her if she was friendly with or saw any of the members from those 1919 days, such as Edna Ferber. “Oh no!” she says. “Have you?” “No, I’ve never met the lady,” Lamparski replies. “Then you’re on velvet!” Parker says. “You think Elmer Rice is cross? Oh my Lord, she’s just mad at everybody and everything.” Ferber was still alive, and living on the opposite side of Central Park from Parker.

“That whole Round Table thing…there was no truth in anything they said,” Parker opined. “They came there to be heard by one another. ‘Did you hear what I said last night?’ Really, it was not the Mermaid Tavern. It was not indeed. People look at it rosily now, and it wasn’t. I promise you it was not good. It was the terrible day of the wisecrack, so there didn’t have to be any truth. There’s nothing memorable about them, about any of them.”

A few choice selections from the interview are vintage 1966. She reads Women’s Wear Daily (“a friend sends it to me”) to keep up on gossip of the Beautiful People (“those idiots, I love to read about them.”) She also follows the news about the growing war in Vietnam, Bobby Kennedy, and the flop that her friend Lillian Hellman wrote the screenplay for, The Chase starring Marlon Brando. Parker said she would love to go to the discothèque Arthur, the first disco in New York, but “the noise is dreadful to me…you have to get the beat.”

Parker says she’s reading James Purdy and James Baldwin, but none of the popular writers of the era: John Updike (“He doesn’t interest me”), Peter De Vries (“just awful”) and more: “You can have Miss Mary McCarthy for your birthday.” She also puts Clare Boothe Luce in last place on any list of good writers: “she is just impossible… she did not write [The Women] she had little assistants and they did the whole thing [Moss Hart].”

Parker does reminisce at times, about names such as Ernest Hemingway and Robert Benchley, and their times together. She also relates an anecdote about the Garden of Allah “a kind of superb idiocy” on Sunset Boulevard: the story is about Benchley and Frank Sinatra. If there is one thing to take away from this interview is that Lamparski pulls it off marvelously, and that Parker is clear-headed and lucid throughout. It appears they did their drinking later.

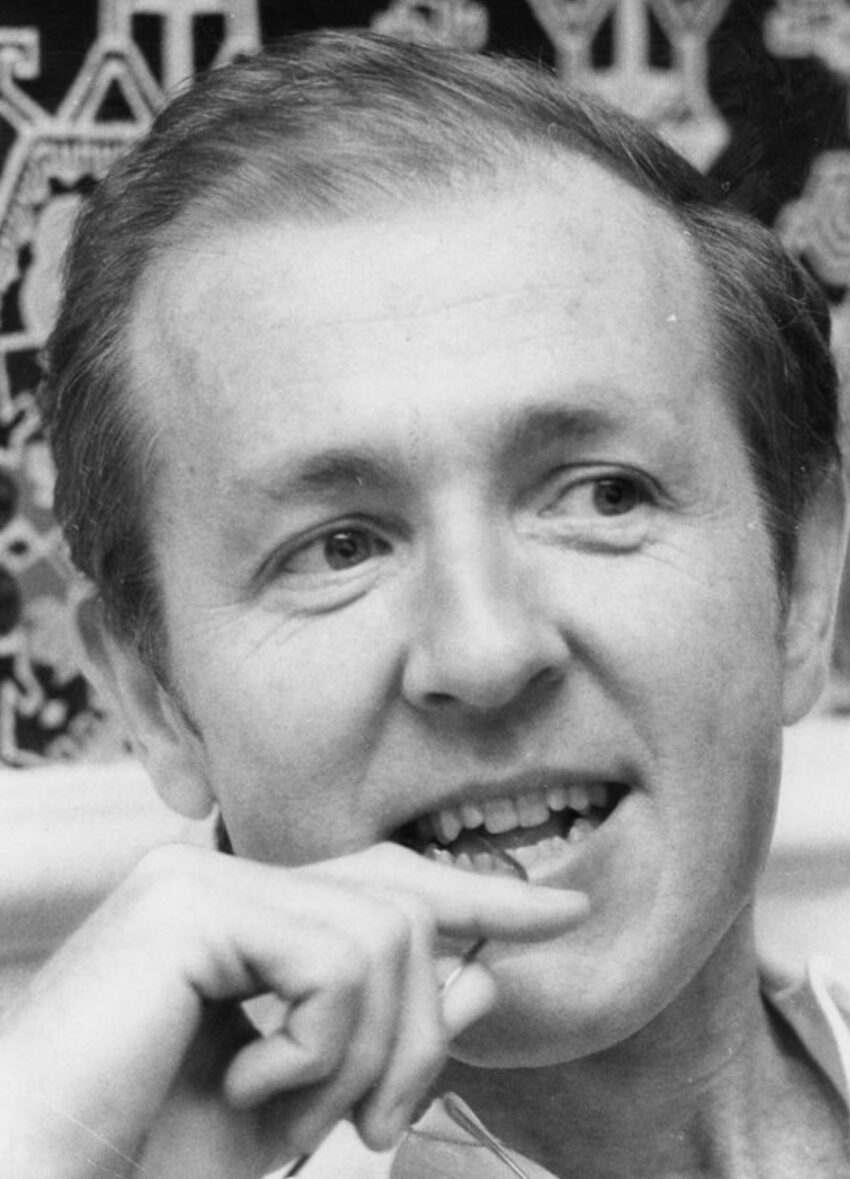

Who is Richard Lamparski? Many old Hollywood fans will recognize his name from his book series Whatever Became of…? but this is not who Lamparski was in 1966. Lamparski was born in Detroit in 1932. He launched his career in 1950s Los Angeles on the periphery of motion picture publicity. Lamparaski relocated to New York in 1960 to try to become a writer. He lived in hotels and hobnobbed with the smart set. Lamparski became a publicity man. Somehow he fell into the world of dealing in gay pornography, collecting and selling it. In the summer of 1964 this got him charged and sentenced to two months on Rikers Island. Once released, he reinvented himself as a broadcaster, launching his interview show on WBAI in March 1965.

He was 33 when he interviewed Parker. By 1966 he had conducted around 100 interviews of stars of yesteryear. His WBAI show was just one year old (it ran for eight). Lamparski hit upon the brilliant idea of tracking down old time entertainers and newsmakers from days gone by. In the 1960s many vaudeville and silent movie stars were still alive, and he searched out these senior citizens. Lamparski would go on to interview more than 1,000 names over his long career, which led to books and television appearances. He retired to Santa Barbara, California, where he lives today and grants occasional interviews. Lamparski is approaching 90 and is one of the few alive who interviewed Dorothy Parker, or took her to the movies.