Dorothy Parker Comes Home

The Ladies Home Journal (New York edition)

March 1965

In moments of family stress my mother often would quote a line or two by Dorothy Parker (“…better a heart a-bloom with sins/Than hearts gone yellow and dry,” for instance, or “I wonder what it’s like in Spain”), and I absorbed them along with A. A. Milne and Mother Goose. Later, in high school, I read her short stories (Big Blonde I remember especially as the height of worldly wisdom), and discovered her part in that institution so dear to the hearts of writers too young to remember, the Algonquin Round Table. By the time I got to college, though, Mrs. Parker had become a figure of mild, literary fun–we were much too erudite to suppose that writing so simple could be any good–but she remained a kind of secret woman friend whose experience of everything from unrequited love to Negro segregation was remarkably like our own.

Finally, when some kindly English teacher had made us understand that “light verse” was a sort of poetry, not a term of derision, I turned to her works again. And there she was, clear-eyed, unphony and astringent as ever: a writer with the voice of her generation, but enough insight and style to make much of her work–as Edmund Wilson and Somerset Maugham predicted 20 years ago–last beyond it.

So it was with some trepidation that I thought about asking her for an interview: meeting long-distance friends, especially writers, is often a mistake. Besides, at the age of 71, in poor health, and newly returned to New York after the death of her husband in California two years ago, it seemed she deserves some privacy. In the end I phoned–hesitantly–the East Side apartment-hotel where she was staying, and made some kind of explanation about the interview; what it was like to be back in New York, how the city now compared with the city in the ’20’s and ’30’s. She waited politely until I trailed off.

“All right, dear,” she said briskly, “we can talk. But not about that damned Algonquin; I’m fed to the teeth with Algonquin.”

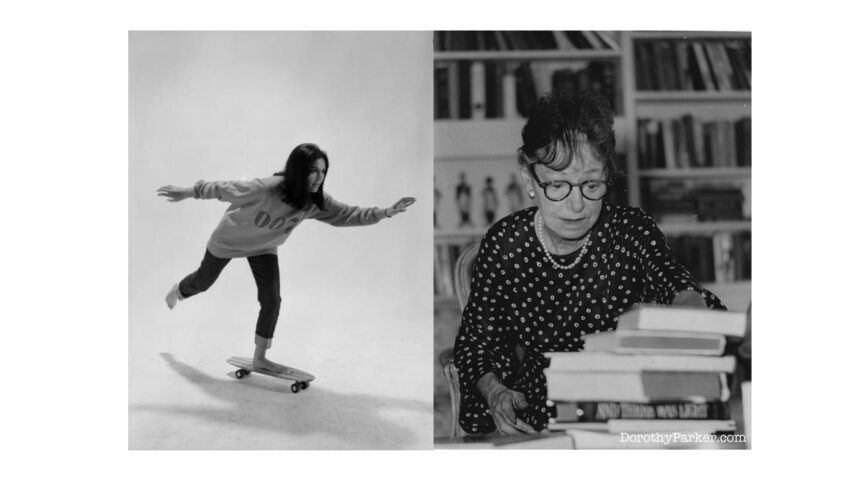

Mrs. Parker, looking frail but gay in a red plaid skirt and red embroidered Mexican blouse, walked slowly to the couch and settled herself next to Troy. “I really don’t need a nurse now,” she explained, “only someone to help me dress and lift things. I broke one shoulder, and then–nature abhors imbalance, I think–I got bursitis in the other.” She lit a filtered cigarette, the simple mechanics of it costing her something, and gestured toward the door. “Nurses,” she said. “They have a language all their own–‘It’s time we took our bath now, dearie,’ that sort of thing–and it drives me mad.”

The only recent photograph of her–a super-realistic close-up taken by Richard Avedon for his book, Nothing Personal–seems cruel and old compared with her liveliness in person: all the signs of age are there, of course, but the dark, soft hair falling over her forehead in bangs (and cropped close at the neck in the ’20’s style she has always worn) and her quicksilver mobility of expression make her seem younger.

“Just look at that plastic tablecloth,” she said, and grimaced. “Isn’t it horrible? The nurse bought it; she thinks it’s very pretty. I try to think of it as pop art, but I can’t–oilcloth, yes; imitation lace, no–it’s too middle class.”

Was she glad to be back in New York? “Oh my God yes,” she said. “I looked forward to it every single day. California is nothing but money and what picture did you do, and Hollywood is a desert, a ghost town. Alan and I (her second husband, actor and playwright Alan Campbell) stayed there because of work–actually, I’ve lived there quite a lot and I hate it more each time. I stayed on after he died in order to close the house and take care of things.” She sighed, and Troy crawled into her lap as if in sympathy. “New York is home, and I love everything about it, including the dirt. It does seem to me that people are a little more unfriendly and cross than I remember–they walk fast, but seem listless: strange–but perhaps I just anticipated too much and was bound to be disappointed. Still, New York is the only place to be in the whole country.”

Had New York–the literary New York of theaters and meeting places and magazines–changed greatly? She looked contemplatively at her feet, the toes of her two red slippers placed neatly together like a child’s. “Oh dear, I suppose you mean has it changed since the Algonquin. That Round Table thing was greatly overrated, you know. Often, it was full of businessmen and publicity people and hangers-on, and a lot of second-rate writers saying, ‘Did you hear what I said the other day?’”

The one man of real stature who ever went there was Heywood Broun. He and Robert Benchley were the only people who took any cognizance of the world around them. George Kaufman was a nuisance and rather disagreeable. Alexander Woollcott was a lonely man with the worst taste I ever knew, but once in a while, he would surprise you with some great burst of generosity. Harold Ross, The New Yorker editor, was a complete lunatic: I suppose he was a good editor, but his ignorance was profound.”

She lit another cigarette, her hands slow, but still fine-boned and graceful, her nails long and paley lacquered. “There are some wrong ideas about those writers. Hemingway, for instance, he was a great brute of a man, difficult and terribly jealous, as you can see now in A Moveable Feast: he discredited everyone in that book, and ended by discrediting himself most of all. Fitzgerald, on the other hand, was kind and generous to everyone; a wonderful man.” She paused, and her voice, always soft, became still softer. “I was just thinking of Woollcott. Did you know he kept a great ledger in which he listed things to do each fifteen minutes of the day? He was afraid of being alone, of having nothing to do.

“Now, of course, there are no humorists at all except Perelman. He must be a lonely man: whom can he talk to? I don’t know why there aren’t any satirists left. I suppose there’s just no demand. Critical writing is at an incredibly low level; it’s a lot of mush, they just love everything. I did like Kenneth Tynan, though, when he was writing here, and I think Judith Crist is good as a movie reviewer. I don’t see movies much anymore, but Tom Jones was so good it will last me for ten years. As for magazines, well, I like The New Yorker, but I do get sick unto death of reading about childhoods in Pakistan. The Paris Review seems to be stuck on one track, though, of course, it originated that track. Contact is a wonderful new magazine that’s put out on the West Coast. Ladies’ magazines seem all alike, but I love reading that terrible ‘People Are Talking About’ and ‘Beautiful People’ trash in Vogue, and I devour every word Eugenia Sheppard writes about all those silly people. Actually, I think the Herald Tribune is getting better, especially the magazine section on Sunday, but it does help to read The New York Times to find out what’s really news. And I like the Daily News. It’s such good, honest rubbish.”

What about the new young writers? Has she found some–perhaps in the course reading for her Esquire book reviews–whom she liked? She smiled, and gestured toward the coffee table. “Well, there’s one good book; I really think Mr. Auchincloss has done an excellent job with The Rector of Justin. Unfortunately, I can’t say the same for Mr. C. D. B. Bryan’s P.S. Wilkinson. It’s so damn derivative. It shows some talent–but that’s the trouble with books that get prizes. The prize committee thinks, ‘Oh we’ve got a prize here, we must be cautious.’ I’m still trying to get through Candy. I’m sick of dirty books, I never thought I would be: must they describe the sex act all the time? I’m afraid some Negro books tend to fall into a pattern, too, though God knows, their problems fall into a pattern, so how can they help it? James Baldwin is a good writer, and a man obsessed with decency, not violence. And I read another book, a novel called God Bless the Child, about Harlem, and that was wonderful. Then there’s Edward Albee—my Lord, but he’s good! I didn’t see Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but I’ve read it and read it. How that man can write!

“I used to like books about Jewish childhoods, but even those are getting to be dirty in the same way; all alike. And it’s a terrible thing to say, but I can’t think of good women writers. Of course, calling them women writers is their ruin; they begin to think of themselves that way. The highest praise is still to say, ‘She writes like a man.’ Isn’t that ridiculous?”

Mrs. Parker gave up writing poetry years ago, and voluntarily. (“Let’s face it, honey,” she explained, “my verse is terribly dated.”) Though Somerset Maugham wrote that her poems displayed “the quintessence of her talent…like Heine, she has made little songs out of her great sorrows,” she is, as usual, her own severest critic: “I was following in the exquisite footsteps of Miss Millay,” she once said, “unhappily in my own horrible sneakers.” She wrote short stories, films, plays and lyrics as well (“I wish to God I could do one [a novel], but I haven’t got the nerve,”) but lately her writing has appeared most often in the book column of Esquire.

“I want to write for them again,” she said, “but it’s difficult with these hands. I can’t really write or use a typewriter yet, and I loathe the idea of dictating. Just now, I’m working on an anthology of short stories with a professor at Los Angeles State College, where I taught for a year–I was a lousy teacher: I hated the pupils, they were so set in their minds, and they hated me–but I’m not quite sure how I got into that.

“And I have a couple of short stories I’d like to write, but I’m afraid they will be rotten. I’m terrified to begin.” Had she always been terrified at the beginning of a story? “Oh, yes,” she said cheerfully, “it doesn’t get better with time, it gets worse.”

Last year she was in the hospital, and this year she is much improved by comparison. (“It’s not really my arms so much as this heart thing.”) But she still goes out of her hotel room rarely and keeps up with the world mostly through books, television and the visits of a few friends. (“A visit with someone is a day in the country! But there are so many gaps in the circle now.”) Television, being her constant companion, comes in for some of her most withering wit: she still, as Maugham said, “seems to carry a hammer in her handbag to hit the appropriate nail on the head.”

Johnny Carson is a television personality of whom she isn’t fond (“He puts in all those dirty little jokes; and don’t you think he’s made of plastic?”), and she was recently startled to hear Les Crane (“Isn’t he awful?”) refer to Emily Dickinson as “Mr. Dickinson… he must have thought it was Emlyn.” The spate of dance parties, bad mysteries and variety shows mystifies her, but she eagerly awaits performances by Nichols and May (“They’re so observant”) and Oscar Levant (“I love him, I’ve always loved him”). That Was the Week That Was is her favorite program, but she watches the various performances of President Johnson & Family with some regret for the loss of style of the Kennedys.

“But, oh dear, I would so like to get out. There are so many plays I’d like to see. I think off-Broadway is the most wonderful development, don’t you? There are restaurants I miss, and I’d love to go to a discothèque.” She looked out the window, caged. “I’m happy to be in New York though, even in this apartment. It smells different.”

It is several hours later and time to go. The visit has been wonderful and, for me, odd: I can’t shake the feeling that I have been visiting some friend of mine–about 30 years old, intelligent, spirited and very much up-to-date–who just happens to be trapped in a 70-year-old body.

“It’s been nice to see you,” said Mrs. Parker. “It does get a little monotonous, talking to the nurse.” She looks at the Auchincloss book lying on the table. “He must be an interesting young man,” she said. “You know, the odd thing about being old is that you see something–something especially good or rotten or funny, and you think, ‘Oh I must show this to so-and-so, it’s just his sort of thing.’” She smiled, and walked slowly to the door. “And what’s odd is–there are so many gaps in the circle now–that so-and-so is gone.”