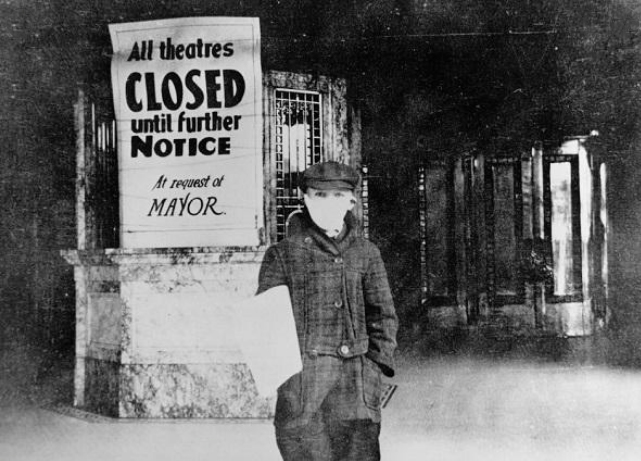

In these heartbreaking times of the coronavirus and fears of a global pandemic, when the outbreak is impacting millions of lives and scores of families have already lost loved ones, many commentators and historians are writing about the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. The mysterious form of the influenza virus killed between 20 and 40 million worldwide; some believe 50 million. In New York City, between 1918 and 1919, more than 19,000 deaths were recorded. There was one day where 851 died in 24 hours. Theaters and schools closed, parades were banned, and city hospitals were filled to capacity. The worst was over by December 1918.

A lot of that sounds like it is from today’s news headlines. Looking to the past, producers closed Broadway theaters, which is something that hasn’t happened yet in New York. Life was disrupted. A little more than a century ago, Dorothy Parker was right in the thick of the pandemic. At the time of the crisis, she was in her first year working at Vanity Fair as chief dramatic critic. She was living alone while her husband, Eddie, was waiting to return home from the Great War. She was 25 years old when New York started closing down.

At first, Parker made light of the situation in reviews. But soon, people she knew, including an actor she reviewed favorably, were among the dead. In the December 1918 issue of Vanity Fair, she reported on the plays that were shuttered. Which may have not been a bad thing for some of the producers.

“There is always this to be said for the epidemic of Spanish influenza—it gave the managers something to blame things on,” Parker wrote. “Whenever a manager saw that all was practically over with a play, he hid his aching heart under the guise of noble solicitude for the public welfare, and, with an air of, “It is a far, far better thing that I do than I have ever done,” announced that the play would be removed, owing to the epidemic. If you are one of those who must ever go about the world finding good in everything, hold the thought that the Spanish influenza has helped many a play to make a graceful get-away.”

“It was a thin month for the drama, one way and another. There was one dark Saturday night when seven plays slunk out into the Great Unknown, among them Some One in the House—and I liked it so much, too—and I. O. U., a dainty trifle in which, as a climax, José Ruben branded Mary Nash on the shoulder with a red-hot iron. Though that Saturday marked the crisis, the lean days are not yet over for the plays. Several of them are tossing fitfully, and two or three seem barely able to stagger through the week. It looks as if the managers would have to call in the aid of influenza again, to get them decently off to the warehouse.”

Among those who died in the pandemic was Goldwin Starrett, the architect of the Algonquin Hotel in 1902. On May 9, 1918, Starrett died of pneumonia at his home in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. He was forty-three years old.

Parker, not one for melodrama, loved the play despite what she called the “trick” nature of the scenario. The handsome raven-haired Hull co-starred in many hits with Billie Burke, Fay Bainter, and Mrs. Fiske. Born in Louisville in 1884, he was a frequent player during WWI and appeared in early silent films. He married actress Mary Josephine Sherwood in 1910. Under Orders, the play Parker saw Hull appear in, would prove to be his last. He was a victim of the influenza pandemic. He died in January 1919 at age 34. The play closed the same month.

If history repeats itself, the pandemic will cease and life will continue as before. Perhaps theaters will close again. But just like 102 years ago, it was momentary, and we recovered.

All information from Dorothy Parker Complete Broadway, 1918-1923 (Donald Books)