In the summer of 1940 PM launched in New York. A daily newspaper that accepted no advertising and pioneered the use of color printing, it was run by Ralph Ingersoll, one of the first editors of The New Yorker. PM would have appealed to Mrs. Parker with its strong editorial stance against fascism and support of President Roosevelt. In October 1940 the book department put the new Ernest Hemingway book For Whom the Bells Tolls in her hands. At the time Mrs. Parker was a screenwriter living in Hollywood. She had a vacation home in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. What she does not say in the review is that she saw the bombing in Spain with her own eyes.

For Whom the Bell Tolls Review

By Dorothy Parker

October 20, 1940

PM

Once I knew a woman who, by a set of circumstances which has been denied my understanding, got herself among people who chanced to be discussing War and Peace. “Now, let me see,” she said. “War and Peace, now, did I read that, or didn’t I? I sort of think I did, but I’m not really sure.”

I shall meet that woman again, for I have little luck in such matters. It will be with those who are talking about Ernest Hemingway’s latest book. “Now, let me see,” she will say. “For Whom the Bell Tolls. Oh, yes, of course I read that. It’s one of those books about the Spanish War, isn’t it?”

I let her go, on the War and Peace affair. But this time she shall die like a dog.

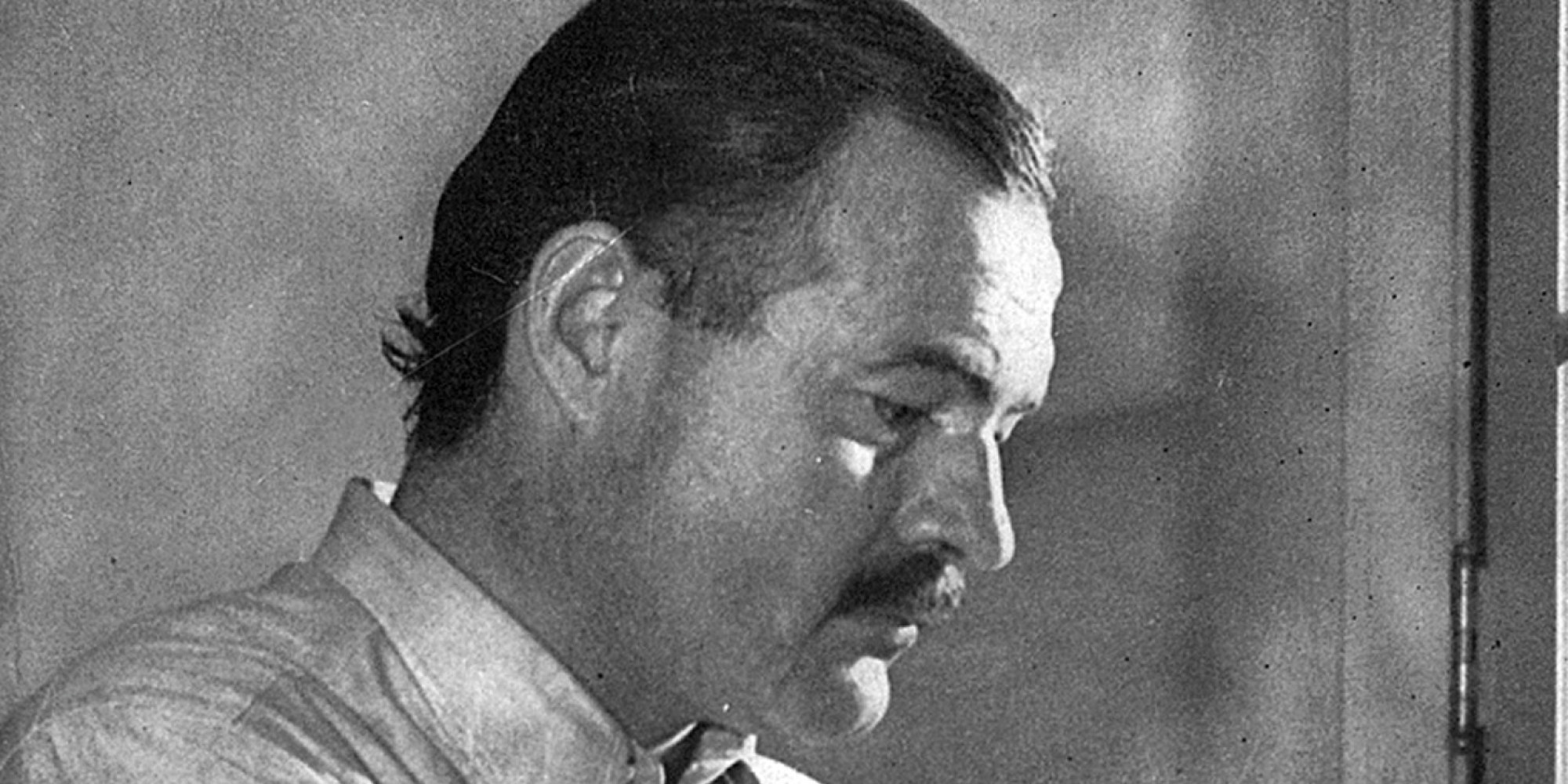

Ernest Hemingway’s new book, that took two years in the writing, spans three days of the war in Spain. The war, they all know now, that should have been won against Fascism, so that this war could never be. Many did not know it then, and that is not terrible of them. But some who were high in power did know, and for their own brief advantage they lied and said it was not like that and everybody should do nothing about it. And theirs is the deed that cannot be forgotten.

This is a book, not of three days, but of all time. This is a book of all of us alive, of you and me and ours and those we hate. That is told by its title, taken from one of John Donne’s sermons:

No man is an Iland, intire of its selfe; every man is a peece of of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were: any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for thee.

This is a book about love and courage and innocence and strength and decency and glory. It is about stubbornness and stupidity and selfishness and treachery and death. It is a book about all those things that go on in the world night and day and always; those things that are only heightened and deepened by war. It is written with justice that is blood brother to brutality. It is written with a wisdom that washes the mind and cools it. It is written with an understanding that rips the heart with compassion for those who live, who do the best they can, just so that they may go on living.

It is a great thing to see a fine writer grow finer before your eyes. For Whom the Bells Tolls is, and beyond all comparison, Ernest Hemingway’s finest book. It is not necessary politely to introduce that statement by the words “I think.” It is so, and that is all there is to it. It is not written in his staccato manner. The pack of little Hemingways who ran along after his old style cannot hope to copy the swell and flow of his new one. I cannot imagine what will become of those of them who are too old for the draft.

There are many authors who have written about love, all along the gamut from embarrassment to enchantment. There are many who have written about sex and have got rich and fat and pale at the job. But nobody can write as Ernest Hemingway can of a man and woman together, their completion and their fulfillment. And nobody can make melodrama as Ernest Hemingway can, nobody else can get such excitement upon a printed page. I do not feel that the creation of excitement is a minor achievement.

For Whom the Bell Tolls is nothing to warrant a display of adjectives. Adjectives are dug from soil too long worked, and they make sickly praise and stumbling reading. I think that what you do about this book of Ernest Hemingway’s is to point to it and say, “Here is a book.” As you would stand below Everest and say, “Here is a mountain.”

***

More lost pieces written by Dorothy Parker will be presented in 2017, the fiftieth anniversary of her death. The Dorothy Parker Society published a lost Christmas story last month.