In December 1916, one hundred years ago, Dorothy Parker was 23 and on the staff of Vogue. She would not be married until 1917, so she was still Dorothy Rothschild. This was her first year working for Condé Nast, her first professional job. Down the hall was Vanity Fair, which accepted this piece of writing. It has not been republished since then. In 2017, the fiftieth anniversary of Dorothy Parker’s death, more lost gems such as this one will be published here.

The Christmas Magazines

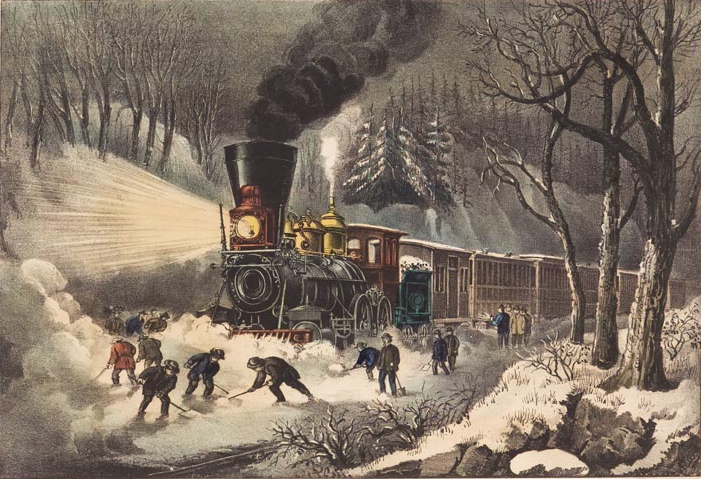

And the Inevitable Story of the Snowbound Train

By Dorothy Rothschild

Vanity Fair, December, 1916

Every year I buy them—the Christmas magazines. Every year I say, hopefully, “Perhaps this time.” And every year I say, wearily, “Never again.”

But I’ll go on buying them, and I know it. Hope does die so hard within me. Somewhere, some time, possibly here, perhaps in Heaven, I shall find a Christmas magazine without the story of the snowbound train.

It seems to be a trait they share with actresses. For the snowbound train story sometimes has an actress in it instead of a lonely old millionaire—though he is first choice, I suppose on account of the child’s future. If it’s an actress, she is always a self-made blonde, a member of a traveling burlesque troupe, and unfailingly has a little golden-haired child of her own, hidden away in the West. Sometimes, to make it harder, she has two little golden-haired children, but the story is just the same—stocking, tree, toys, etc., etc.

That’s the story. If they have ever published a Christmas number of any magazine without it, it must have been before I was born. Words are powerless to convey the loathing which I have for that story. It ruins the holidays for me. I buy hordes of magazines in the hope of finding one—just one—without it. But there it always is. Even Snappy Stories has it—the actress version, of course. And the horrible part of it is that when I see the title “Christmas on the Train,” or “A Snow-Bound Santa Claus,” or “A Little Child Shall Lead Them,” or any of the hideous titles under which it masquerades, I cannot drop the book and run. No, a morbid fascination makes me read every word of it. Perhaps I shall have my reward, some day. Perhaps it will be my lot to discover the radical spirit who will give that child dark hair.

And the rest of the average Christmas number is no better than that terrible story. Look at any one of the magazines. They are just the same this year as last. The verses may be a bit freer, but that’s all.

The first page is always given up to a highly decorated poem. You know the kind, one of those poems with mediaeval spelling. It is one of those hearty, good-cheer things, and it usually contains frequent requests to “let the welkin ring.” Just what is a welkin anyway? I wrote one of that kind of Christmas poem a week or so ago, just to see if I could do it. I sent it to a poor little magazine that hadn’t many friends, and I had such a nice note from the editor, saying that he would be most glad to accept it. That was all. I shook the envelope, but nothing fell out. Do you know what I am going to do? I shall give him one more week, and then I shall write to him and tell him that he is under a misapprehension—my contribution was not meant to be free verse.

Then come the stories. The one about the burglar who the child thinks is Santa Claus—you know that one, don’t you? Then the strong, red-corpuscled one about the half-breed’s Christmas. And the misery story that starts, “She counted them again. Seven cents—seven worn, thin, sweat-stained pennies, and to-morrow would be Christmas!” And the sweet, sweet, sweet little tale of Christmas in the old South. And the one about the erring wife who comes back to her husband, or the erring husband who comes back to his wife—it depends on whether a man or woman writes it—just as the Christmas chimes ring out on the old village clock. Then there are the “Christmas in the Trenches” articles, and the masterpiece in Harper’s which is always called “Christmas in Many Lands.”

Then there is the double-page spread about how certain actresses spend their Christmas at home. There they all are—the vampire lady, the heroine of the glad play, the musical comedy star, and all the rest of them, photographed at home, exclusively for every magazine on the news-stands. One gathers from the photographs that these ladies carry their art into their home and holiday life. The vampire lady, for instance, wears one of those home-wrecking gowns, drapes herself over an evil-looking divan, and spends a merry Christmas leaning on her elbows and looking at a skull. The heroine of the “glad” play is perched girlishly in the middle of her dining-room table, hugging a Teddy bear and smiling sunnily—for it is Christmas, and a blizzard is raging, and all the trains are tied up, and thousands of people are freezing and starving to death, and she is glad, glad, glad. And the musical comedy star is photographed in pink silk pajamas (the picture isn’t colored, of course, but you just know they’re pink). She is on her way to enter her holly-wreathed bath-tub, but she has paused for a moment to gloat over the brimming stocking which hangs by the fireplace—though goodness only knows why a filled stocking should be any treat to her.

Then the pages and pages of What to Give. Oh, how I skip those pages! That awful page headed “Gifts for Her,” with its scentless sachets, and its timeless wristwatches, and its Harrison Fisher calendar with a lady and gentleman executing a different kiss for every month of the year.

And always there is that page of jokes. “Christmas Jests,” they are called, instead of the usual “Sense and Nonsense” or “Verse and Worse.” They are the customary little parlor anecdotes that you cannot remember even while you’re reading them, made timely by the use of such phrases as “said Willie, passing his plate for more plum-pudding,” and “Mother asked, as she trimmed the tree.” There is nothing on earth so serviceable as a joke. Later on, these same jests may be successfully used for the July number by the simple method of changing the Christmas phrases to “said Willie, as he stooped over the lighted firecracker,” and “Mother asked, as she bandaged Baby’s eye.” I read the jokes through quickly, dread in my soul. I always expect to find the snowbound train tale among them, considerably condensed, and with the fun lying in the train-hand’s remark to the Lonely Old Millionaire.

I bought all the Christmas numbers this year. Just at present I am deep in the “never again” stage. But I shall probably buy them again next year—I feel it hanging over me. Oh, is there no great public-spirited soul, no intrepid reformer working for the future of the race, who will found a Society for the Suppression of Christmas Issues?