On Writing Biographies: Kevin Fitzpatrick interviews Marion Meade about Buster, Woody, Zelda, and Mrs. Parker

Interview by Kevin C. Fitzpatrick, December 2006

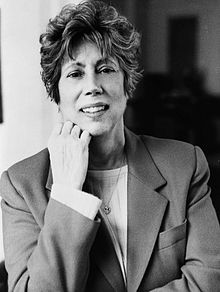

New York author Marion Meade has written a dozen books, but it is her biographies that she is proudest of. Meade is perhaps best known for delving into the lives of 20th Century icons. Her most recent book, Bobbed Hair and Bathtub Gin: Writers Running Wild in the Twenties examined Zelda Fitzgerald, Edna Ferber, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Dorothy Parker in one ten-year period. Meade wrote about two filmmakers in Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase and The Unruly Life of Woody Allen. Her 1987 biography Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? is the definitive Parker bio; in 2007 Penguin Books is releasing an updated 20th anniversary edition of the book. Meade’s next project is a joint biography of Nathanael West and Eileen McKenney, due out in 2008 from Harcourt. She took time to sit down with Kevin Fitzpatrick in her comfortable Upper West Side apartment.

Kevin Fitzpatrick: What’s the most rewarding thing about a good biography?

Marion Meade: By looking into another person’s life, you need to look into your own. Whether you are the biographer or whether you are the reader. It’s like truth is stranger than fiction. When I am reading a biography, there is something more rewarding about reading about a real person’s life, rather than fiction.

KF: How did you pick biographies as your field?

MM: My background is that I went to journalism school and I started out to be a journalist. I never considered writing books. I was more interested in magazines and newspapers. But as it turns out, journalism, and what you do as an investigative journalist, is exactly what you have to do for biography. Biography was traditionally written by people who had lots of money and didn’t have to do anything (laughs). Or – when I first started out – they were done by academics. Most of these people had very strict rules for what they thought was appropriate for a biography. They were very stuffy. They thought you had to be very circumspect. You couldn’t really pry into a subject’s life, which to me sounds insane, because that is what I do: I pry into people’s lives. So I am perfect for what biography has become today because there is nothing I wouldn’t investigate (laughs). And there is almost nothing that I wouldn’t print, if I could. That is the way that biography has changed in the last 20 years. It was a kind of white glove type of writing, now it’s “anything goes.” There are different categories of biography, and celebrity biography is one of them. It is almost considered not a legitimate type of biography. Biographies were always about people who were dead. Today, very often, they are about the living.

KF: What would you tell a writer who is thinking about writing his first biography? What background or skills does he need?

MM: First of all there is no place to study to become a biographer. There may be a course or two here or there, but you can’t study or prepare to become a biographer. I have also noticed very often that biographers are not young. You don’t see too many biographers who are in their twenties, or even their thirties. Somehow people aren’t drawn to this sort of writing until they have some maturity. After all, you are taking another human being’s life, and you are dissecting it, you are interpreting it. And if you don’t have any life experience yourself — or a limited amount when you are young — it’s just overwhelming. You don’t have the background to make what is a satisfying biography. What I can say is that biography can be compared the most to being an investigative reporter. I still think journalism is the best preparation because you are doing the same thing. A reporter has a couple days or a couple weeks to do the research; a biographer has a couple of years. But it is exactly the same process.

KF: What is the difference between writing a biography of Marie Antoinette and of Katharine Hepburn?

MM: It really doesn’t make much difference if a person has been dead for 600 years, or whether they died ten years ago, or whether they are still alive. You still have to do the same job.

KF: But a person writing about 17th Century France is not too likely to discover a box of letters in someone’s attic; whereas someone who is writing about a 20th Century popular culture figure would have a better chance to present new discoveries.

MM: With people who have been dead for centuries, and if you undertake a biography of someone dead that long, there are usually always documents. Usually they are the same set of documents and source material that anybody else can find. Very, very rarely do you find something that is new. And if you do find it, it’s usually in the newspaper first. It is nothing you could find by yourself. People who died in this Century, there is a good chance of finding something on your own. Something that’s not been concealed, but something that has not been available. By doing your research you find someone who has this material. The third type of research is when the person is alive – and definitely doesn’t want you to have anything of theirs (laughs). For all three types, whether (the documents and leads) have been there for centuries, whether it’s not going to be there, or whether you have to find it, it is all the same process.

KF: What are the difficulties or challenges when your subject is still alive? I know you had a lot of problems when writing your book on Woody Allen.

MM: Well my experience with Woody was pretty much what most (biographers) experiences have been with a living person. Although there are many living people who say that they will cooperate. In fact, very often, they don’t. They cooperate up to the point where they see what you have written. I found it very interesting that a lot of biographers would do dead people, but you would have to put a gun to their heads to make them do a biography of a person who is alive. I rather thought this would be interesting. And it was. But I felt I picked a person who, first of all, wasn’t going to cooperate with me, and I didn’t want him to. He was known as a very litigious person, who sues a lot of people left and right (laughs). I felt in some way that he’d try to harm me. That wasn’t really paranoid. I had a friend who wrote a biography of John Lennon. His name was Albert Goldman and this was in the late eighties… He became so paranoid, not paranoid of Yoko Ono, that before the book came out he left the country, he moved to Germany for six months. So I consider that the ultimate in paranoia. But everyone who does a biography of a living person, who is oppositional with their subject, is afraid they will be damaged. And the way you can be damaged is they will sue you, and most publishers will not help you. I think that for Woody my publisher did have a miniscule insurance policy (laughs). But most of the time you are on your own.

KF: Would you write another biography of a living person?

MM: I don’t think I would. I did it. I saw what it was. I’m glad I did it (laughs). But I’d rather move on.

KF: Aside from your two books about Medieval France, you seem to focus more on Post World War I Americans. Why do you like that era?

MM: I like to write about writers. I like to write literary biographies. I like to write about people in the theatre and people in film. I’ve written a couple of books about film people. And Dorothy Parker was half a film person. I can relate to a lot these people because sometimes they were alive during my lifetime. Parker was alive during part of my lifetime. I get a lot more satisfaction because it’s part of history that I remember. Now I’m writing about a person and part of it takes place in the Depression. For example, nearly all the people I’ve written about lived through the Depression. I was born in the Thirties. There is something very satisfying about having lived through a piece of history that your subject has lived through. And also, I like people who have lived where I’ve lived. That’s why I like New Yorkers.

KF: Most of your subjects could have all been in the same room together. Buster Keaton, Zelda Fitzgerald, Parker…

MM: Right. In fact I like to pick subjects who knew each other. When I was interviewing people about Dorothy Parker, especially people who lived in Bucks County, they would start talking about Parker and the next thing I knew they were talking about Nathanael West. These people associated them together, and Parker and West did know each other, so it’s like it’s all family and it all kind of builds, which I find very interesting. To go now and do a biography of someone who wasn’t from New York, who wasn’t in theater or film, or wasn’t a writer, I would have to do a lot more work because I’m unfamiliar with the bedrock of where that life was rooted.

KF: So no Winston Churchill for you to write about?

MM: No. But there are people who will, because one subject builds on another. Sometimes you are doing a subject, and there is a Zelig, a little face in the corner. And years later that faces comes up again, and you’ll do that person. I don’t know how these things happen, but very often they do.

KF: Talk to me about publishers. How do they treat biographers? Do publishers like biographies?

MM: Publishers love biographies, even though they always claim they never make any money on them. So therefore they have to offer a very low advance. But acquiring editors adore them. Most acquiring editors will look for something they think will sell a few books. They are not altruistic at all. They are thinking, “Oh, who’s going to read this?” and “How many copies can I sell?” They are also in a way useless and stupid because they are of no help to a biographer whatsoever. They don’t know anything. Very few of them know anything about anything, really. For example, I would think that most editors would know something about American literature. But in fact they know very little. So therefore they can’t fact-check a book. Even in a global sense, if they see something there they can’t say, “What a minute, is this really right?” They can’t challenge you. Because they are at a disadvantage. They are being presented with material… and very often they let things go by that they should have stopped simply because they have too many books to edit. They can’t get involved with any one book. They are more concerned with you making your deadline. Which is, from my point of view, is too bad. Very often there is nobody to count on. They don’t edit biographies, even though they are supposedly called editors. Again I guess it is because they are overworked.

KF: What is the best kind of editor for a biographer to work with?

MM: Somebody who has background in that subject; even if it’s a vague background. Someone acquiring, for example, a political biography or American history, should have some vague knowledge of American history (laughs). You would think that would be a good thing, but that doesn’t happen very often.

KF: For your work today, how have your writing and researching methods changed over the years?

MM: I think now my biggest research tool is the Internet. And I know many old-timey biographers would say, “The Internet! How do you know if something is true or not! Oh that’s a very dangerous way to proceed.” There are things I do now that I would never have done before. For one thing, I now use research assistants. There is a fear among some biographers that you have to do everything yourself. You couldn’t possibly trust anyone to do anything for you. That’s just wrong. I do lots of interviews, perhaps hundreds of them. I can’t go and visit all of these people. I do phone interviews. Again, that was a no-no. I believe in outsourcing. For example, I used to do all my own genealogy. And I wasn’t too great at it. So I’ll use genealogists.

KF: What are things you see writers doing right, and wrong, in biographies on the market now?

MM: There are biographies that I hate. These are the ones where the writer is in love with the subject. It used to be called a puff job; well there are still biographies that are puff jobs. Where the writer doesn’t delve deeply enough in order to really find out who that person is. They start with an infatuation and they never get past that. These are biographies that are usually unsatisfying (laughs). For a biography to be worthwhile it has to dig up everything it can. Once you start digging into a person’s life, any person, no matter who they are or how wonderful they seem to be, you are going to find so much garbage. You’re going to be drowning in it. A lot of biographers, even experienced biographers, will think, “I thought this person was nice. They are really horrible!”

KF: You’ve said in the past that when researching Dorothy Parker, you got turned off to her alcoholism and her lifestyle. You had to take a break.

MM: Right (laughs). With that, it was not my first biography. I came to that in a peculiar way. She was a person who I had admired as a teenager. I had maybe 20 or 25 years to fantasize about what she was like. I had my own picture of her, and it was a horrible shock to find out my picture of her was wrong.

KF: What are some of the benefits of the biography field?

MM: One thing that is great about being a biographer, or that people don’t mention or think of, when you do a book with living sources and you spend time with these people. I can’t tell you how many friends I’ve made over the years. People that I’ve gotten to know, just fascinating people. Some are your friends… until the book comes out. And then they hate you (laughs). But others, who don’t have their egos involved… I can’t tell you how many people I’ve met.

KF: You also get to go to some fantastic apartments too! Fifth Avenue, Park Avenue…

MM: (Laughs). Fantastic places. Fantastic apartments. I’ve been all over. And sometimes people will come to my apartment. That’s always fun (laughs).

KF: Who’s been the most fun person to come over? That totally charmed you?

MM: Woodie Broun. (Heywood Hale Broun was the son of Algonquin Round Table members Heywood Broun and Ruth Hale). I will never forget him. Actually, he sat right where you are sitting.

KF: Are you doing anything to help other biographers?

MM: When I finish a book I believe in giving away my research or making it available to other people. This is not something biographers used to do. They used to keep all this stuff. But I either give it or sell it – especially to some special collections – so that other people can use that material. I feel very strongly that you shouldn’t hide things or keep it, if it can be used by someone else. [Some of Meade’s papers are in the Columbia University Rare Books and Manuscripts Room. – Ed].

KF: Can you tell us one thing about Nathanael West? Or do we have to wait until 2008?

MM: (Laughs). I have a folder called “Crimes and Misdemeanors”… and Nathanael West, of all the important writers of the 20th Century, was probably the biggest criminal (laughs). He did so many things that were not acceptable to polite society.

Thank you.

Kevin C. Fitzpatrick is the author of A Journey into Dorothy Parker’s New York; Marion Meade wrote the foreword. His next book is on the members of the Algonquin Round Table. In 1999 he founded the Dorothy Parker Society, and serves as its president. A freelance writer who lives in Manhattan and Shelter Island, New York, Kevin’s claim to fame is that during his career he has been paid to attend baseball games, drink cheap beer, and read comic books.